Is your photo candid or was it staged?

Ask a Street Photographer this question and you only have yourself to blame for the war of words that ensues. The indignations will run the spectrum. From “How dare you question my integrity?” to “Who cares if it’s candid or not? It’s either a good photo or it isn’t.”

Street Photography is not Photojournalism. The latter carries an implied ethical responsibility to showcase reality that the former does not. When it was uncovered that Giovanni Troilo staged a scene in his documentary series on Charleroi, Belgium, many demanded that he be stripped of his ‘World Press Photo’ first prize. Eventually he was, but supposedly for different reasons.

If instead these were the ‘International Street Photography Awards’, would the reactions have been the same after finding out the photo was staged? Yes they would have been. Without a doubt. So if Street Photography is an artistic pursuit and doesn’t have any inherent attachment to reality, why does candidness matter?

The short answer is: because Denis Diderot said so about painting around 250 years ago, and since photography is a young art form, it inherited all the rules from older art forms, mainly painting and theater, including Diderot’s ideals.

But the short answer isn’t going to cut it, now is it? Let’s trace our steps.

In 18th century France, the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture scheduled exhibitions, or salons, for its painter members in Paris. Denis Diderot, encyclopedist, art critic, and all around wunderkind, was asked to review these salons. He did so for over two decades, crystallizing along the way the tenets of the ideal painted scene in the Age of Enlightenment’s waning years.

Diderot disliked ‘mannered’ people and disliked ‘mannered’ paintings that included them as subjects. “Maniéré”, the word he used in French, is chock-full of negative connotations about artificial behavior. He saw pretentiousness as a “vice of regulated society”, and attributed them to ‘theatrical’ people who act one way when alone and the opposite way when they know they’re being observed.

He saw that the sure way to rid a painting of any affected characters, and thus to cleanse it from any ‘theatricality’, was to have its characters be so engrossed and so absorbed by the action they’re undertaking, that it would be impossible for them to notice they are being watched, and consequently incapable of acting artificially. The beholder — first the painter, and then the viewer — must disappear; the scene is not meant for their eyes. This self-forgetfulness, or oubli de soi, that the characters exhibit is the guarantee of the anti-theatrical ideal.

To showcase this pictorial practice, here are two paintings by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin: Soap Bubbles, and the Card Castle.

In Soap Bubbles, the man is so focused on his task that he seems unfazed that his shirt is ripped near his shoulder. In the Card Castle, the ‘proof’ that the boy doesn’t know he is being observed resides in the open drawer in the foreground. His unbridled attention is directed towards the folded cards in front of him; he can’t see the Jack of Hearts, but we can. Given the medium’s limitations, anti-theatricality was implied through these compositional means, and it was left to the viewer to sense whether a character’s absorption is genuine or not, and whether the fourth wall separating the painted stage from the beholders is unbroken or not.

Diderot’s aesthetic ideals remained influential well into the 20th century, crossing over into other art forms. It isn’t known if philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was borrowing from Diderot when he wrote the following in 1930, but it’s hard not to see the similarities:

“Nothing could be more remarkable than seeing someone engaged in some simple everyday activity, when he thinks he is not being watched. Let’s imagine a theatre, the curtain goes up & we see someone alone in his room walking up and down, lighting a cigarette, sitting down, etc. so that we are suddenly seeing someone from the outside in a way we can never see ourselves; as if we, so to speak, witnessed a chapter from a biography with our own eyes, – surely this would be uncanny and wonderful at the same time. More wonderful than anything that a playwright could produce to be performed or spoken onstage. We would be seeing life itself.”

It was only a few years prior that the 35mm camera had started becoming popular. It was portable, lightweight, and inconspicuous enough that photographs could now be taken without subjects taking notice and altering their behavior for the camera. Photography, the only medium that could genuinely put into practice Diderot’s philosophy and Wittgenstein’s view of “life itself”, was ready to take over.

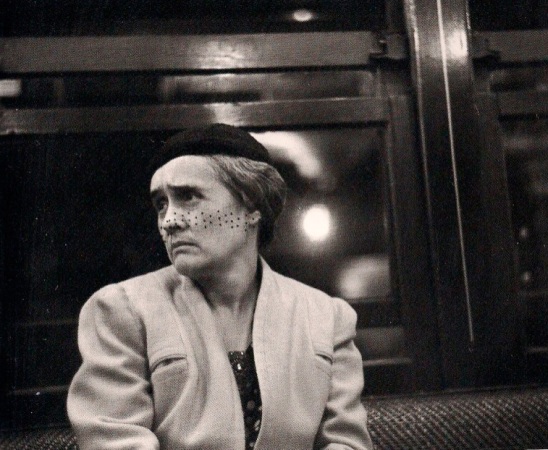

In 1938, fresh off his work photographing for the Farm Security Administration, Walker Evans did exactly that. He took a seat on the New York subway, hid his camera inside his coat, and for three years he sought to capture on film the ever mysterious “quality of being”. In “On Photography”, Susan Sontag would corroborate: “There is something on people’s faces when they don’t know they are being observed that never appears when they do… their expressions are private ones, not those they would offer to the camera.”

The tradition of Candid Street Photography evolved in the following decades, reaching mainstream popularity following Henri Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’. It was then that this tradition became closely associated with the Street Photography that we know today.

But after relying for centuries on ideals borrowed from different mediums, photography would have to wait until 1980 for Roland Barthes’ seminal book, “Camera Lucida”, to give Diderot’s notes on anti-theatricality their own photographic character.

Barthes essentially differentiated between what he referred to as the studium and the punctum. The studium is what the photographer intended to show us in a scene. It consists of the elements that might be interesting to us; those from which we would express a general liking of the photograph.

The second element is what breaks the studium. In the words of Barthes, it is something that “goes from the scene, like an arrow, and pierces me.” The latin word aptly used to describe this wound, this prick inflicted by a sharp object, is the punctum. He saw photographs that only had a studium and no punctum to be lukewarm, bland, and uninteresting. Because the studium was restricted to the photographer’s intentions. And he remarked: “Certain details prick me. If they do not, it is doubtless because the photographer has put them there intentionally.”

Roland Barthes’ view, however influential, remains one voice among many. Evidently, other artistic approaches to photography have attributes that Candid Photography is unable to match. There are even ethical concerns about privacy violations in an age where public surveillance is becoming increasingly common and intrusive.

However, Diderot’s remarks about theatricality being the vice of regulated society rings truer today than it would have at any other time. In our days where almost everything is staged: from public personas, to carefully manicured Instagram feeds and facebook timelines, to airbrushed selfies, candid photography seems to be a tiny antithesis to inauthentic behavior. This type of photography still shouldn’t aspire to show ‘reality’ the way photojournalism is supposed to, but it is obliged to remain firm in its portrayal of ‘realism’ when there are barely any sources left to do so. Otherwise, be candid; don’t call it Candid.

Sources:

- Barthes’ Punctum, Michael Fried

- La Chambre Claire: Notes sur la photographie (Camera Lucida), Roland Barthes

- Staging Absoprtion and transmuting the everyday: James A. W. Heffernan

- Les Salons de Diderot: théorie et écriture, Pierre Frantz and Élisabeth Lavezzi